Dave Buckhout .

Publication Date: June 5, 2012

Over the years, I have developed a special friendship. It often seems a bit of a one-way relationship, no out loud conversation or interaction to speak of between this friend & I. We see each other rarely: once, twice a year tops—and then only 15-20 minutes at a time. Some might question the health of this friendship based on what I have said so far; but I assure you, the bond is tight and grows stronger with each visit. It may help for me to explain that this individual lived in the mid-late 18th century and has been dead and in the ground since 1777: Serj (ye olde abbreviation for sergeant) Elisha Benton.

Over the years, I have developed a special friendship. It often seems a bit of a one-way relationship, no out loud conversation or interaction to speak of between this friend & I. We see each other rarely: once, twice a year tops—and then only 15-20 minutes at a time. Some might question the health of this friendship based on what I have said so far; but I assure you, the bond is tight and grows stronger with each visit. It may help for me to explain that this individual lived in the mid-late 18th century and has been dead and in the ground since 1777: Serj (ye olde abbreviation for sergeant) Elisha Benton.

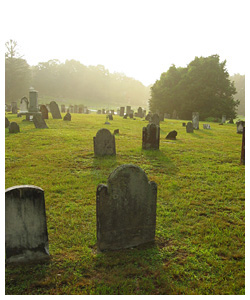

Summer is the usual time when I’m able to return to my hometown of Tolland, Connecticut, and visit with my old friend, Elisha. But I am not always able to make it out to the colonial / Revolutionary War era burying ground where he keeps his centuries-long vigil. In those off-years, it gets me to thinking back on the first time we ‘met,’ a moment of pure synchrony . . .

In September 1994, I was in Connecticut to attend the wedding of 20th (and now 21st) century friends of mine. While there, in a region filled with colonial-era townships, it struck me that I’d never fully appreciated the historical depth of my hometown. It is a common affliction: you don’t view the settings of your everyday life as a tourist would. You rarely think about it that way, especially when young. Such was my own case. In the midst of growing up, it had rarely—if ever—struck me that where I grew up was so unique, a serious oversight that I set out to correct right then. And the first place that came to mind was the colonial / Revolutionary War-era section of the cemetery off Cider Mill Road. It was overcast, the first hints of fall. I was all alone as I walked up the hill past the modern-era section (still in use) towards the olde burying ground. I could only recall being in that cemetery a few times, the only time of significance being a grade-school field trip for the purpose of gravestone-rubbings (a common field trip activity for New England kids). In my teens, I’d driven past it dozens of times without stopping. If I even considered the history of the plot since that field trip, it registered as unremarkable; which, looking back, is simply remarkable—and not in the good way: in a dumbfounded, forehead-slapping, head-shaking kind of way. I went away to college at age 18, was back a few summers after that before moving on for good by age 21. And perhaps that was the best thing I could have done: being so far removed allowed me to look back and realize the remarkable historical settings that had surrounded me in my own backyard.

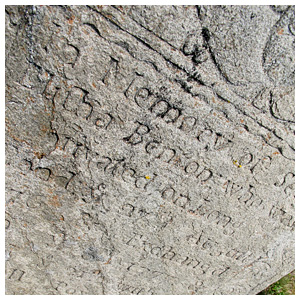

As I made my way through the old section where the first generations of townspeople had been laid to rest, that overwhelming sense of presence and significance so prevalent at landmark historical sites flooded my mind. An amateur photographer, each step was also serving up a perfect frame. But I did not stop. As if compelled, I was drawn to one headstone in particular. I can now recall how odd it seemed, bypassing dozens of fascinating headstones—large & small, granite & red-sandstone, some broken, others so worn the inscriptions were unreadable—heading straight for one rather plain granite marker far in the back. I came up to it and stood before it, looking over its worn-face. It had settled over the centuries, cocked to the right. The inscription was so worn by long hard years of New England weather that I had to kneel and run my fingers over it at points—like reverse Braille—to make it all out. But once I had, I stood back up and stared at it for a moment—stunned: the magnitude of personal history embedded in the story etched onto this headstone, the fact that this story was no exception but more so the norm for thousands of other similar personal histories, those who had helped create this town and the country I had taken for granted . . . Well, I was just stunned. It was an incisive moment of realization, of all that had come before me and delivered me to such a comfortable life. The inscription (full of the olde English use of “f” for “s” and the interchangeable use of “g” and “j”) read:

In Memory of Serj

Elifha Benton who was

captivated on Long

Ifland y 27th Auguft

1776 & Exchanged

Jan y 3d 1777 &

died y 21st with y

Small Pox & in

y 29th Year of his

Age

Wow . . . I had read of how trying the summer of 1776 was for the Patriot cause, of the disastrous campaign to fend off New York from the invading might of Howe’s British regulars and mercenaries—drubbings so complete that the war was almost lost right then & there. I had also read of the thousands of American captives taken during the campaign and how they’d been inhumanely packed into disease-ridden warehouses, or worse: the floating hulls of decommissioned ships. Elisha had been one of those miserable men. I also knew that as the ‘captivated’ contracted disease (mainly smallpox) and became no longer a threat as fighting men, they were exchanged or just outright released. Such was the case with my old friend, who came home from New York to die in January 1777 . . . The weight of this story, of brave civic sacrifice having led not to a long honored life in a free democratic land, but instead to a degrading defeat punctuated by a torturous death in the prime-of-life . . . Again, I was stunned: by the story, by the experience, by the synchronous circumstances that had brought me to Sergeant Elisha that morning.

And yet, as humbled as I felt—really, not feeling worthy to even be standing at the grave of this man—I felt no sense of: “show some respect for your elders, those who sacrificed all for you.” There was no hint of a Puritan-style guilt trip, no haranguing. Honestly, it seemed Elisha only wanted to reach out—to tell his story to someone he knew would appreciate it. ‘As you live your life, on occasion tell the story of my life.’ That seemed his only request. But, I also got the sense that my new—old—friend would enjoy some company every so often; if only once-a-year, 15 minutes at-a-time. In relation to his long vigil, I figure that doesn’t seem like too long a wait.

I cannot promise to make it out each-and-every summer, my old friend. But I will visit as soon as I am able, and will continue to do so for as long as I am able. That is a promise I will keep.

POSTSCRIPT: Having spent the first 18 years of my life in Tolland and having been on (if having not paid attention) the mentioned school trips, it came as a surprise to learn after writing this piece that Elisha Benton was not actually buried in the Benton family plot within the cemetery off Cider Mill. Due to his death at the hands of the darkly feared “pox,” his being put to rest in the public burying ground was not, by statute, allowed. And yet, having discovered that he was actually interred on Benton family land about a mile away—his true love, Jemima, eventually to reside alongside him (see “Forever, Side By Side” below)—and that what I had been drawn to was but a memorial marker, has not lessened the emotion and “moved-by” feeling I get when visiting my friend, the Sergeant. If anything, it seems proof enough that it really is in the spirit of things where core essence resides.